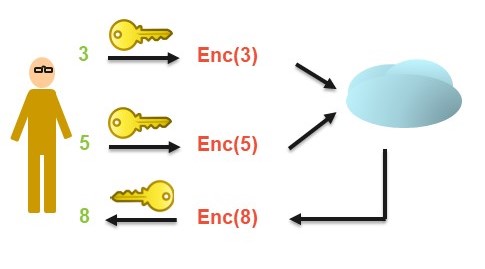

The data told a clear, if subtle, story: users shown fewer positive posts wrote slightly more negative updates, while those shielded from negative posts used measurably more upbeat language. Fractions of a percentage point per person added up to millions of words across the sample. A secondary finding, noted by Cornell communication scholar Jeff Hancock, was a "withdrawal effect"—feeds stripped of emotional content prompted people to post less overall, according to a contemporaneous report in the Cornell Chronicle.

Because no one had clicked anything resembling informed consent, what began as a routine product test erupted into an ethics firestorm. Could a boiler-plate terms-of-service clause double as a biomedical release form? Facebook’s Adam Kramer later apologized in a personal post, yet the episode left a sharper lesson: with enough behavioral data, mood becomes just another adjustable variable.

What One Week Revealed

Inside that seven-day lab, an automatic sentiment filter tagged every English-language post from a user’s friends. The software then withheld a random slice of messages tilted either positive or negative. When upbeat posts disappeared, gloomier status updates followed; when negativity was trimmed, cheerier words crept in. The effect was modest for any single person, but across nearly 700,000 feeds it nudged millions of words and demonstrated that emotional states can migrate through text alone.

Backlash came swiftly. Bio-ethicists argued that a click-wrap contract cannot substitute for informed consent, and scholars pressed journals to clarify rules for industry-academic collaborations. More than a decade later, no U.S. statute requires platforms to log large-scale behavioral experiments. The Federal Trade Commission can act only when such practices cross the line into “unfair or deceptive” territory under Section 5 of the FTC Act, as the agency describes in its enforcement overview.

More Technology Articles

Echoes From Earlier Screens

If Facebook’s study shocked the public, history offered warnings. In 1938 Orson Welles’s radio play “War of the Worlds” used fake news bulletins so convincingly that pockets of listeners fled their homes—an incident later dissected by Princeton sociologists and retold by Wired. The broadcast predated cookies and click-through rates, yet showed how media realism can outrun audience skepticism.

Two decades later, rumors of subliminal theater flashes—"Drink Coke" on a single film frame—sparked congressional hearings. Evidence proved thin, yet the scare widened public awareness that persuasion might happen below conscious attention, an idea modern recommender systems operationalize with algorithmic precision.

Fast-forward to 2016 and Russia’s Internet Research Agency weaponized Facebook’s own targeting tools to reach an estimated 126 million Americans with divisive memes, a scale detailed in U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee testimony archived at Senate.gov. Two years later, the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed how a personality-quiz app vacuumed up to 87 million profiles for election ads, prompting Facebook’s deepest privacy reckoning yet.

Thread those moments together and a through-line appears: each advance in audience measurement—from Nielsen diaries to real-time behavior logs—shrinks the distance between watching and nudging, between seeing and steering.

The Arms Race, 2020–2025

The past five years have turned that through-line into a feedback loop. TikTok’s "For You" feed, trained on billions of signals, now predicts what will keep a teenager glued for hours. A 2024 systematic review in European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry linked heavy TikTok exposure to higher rates of anxiety, body-image stress and self-harm ideation among adolescents.

Generative AI has meanwhile slashed the cost of deception. Off-the-shelf software can fabricate a convincing political-endorsement video in minutes. At least twenty-two U.S. states have passed election-season deep-fake laws, and in April 2025 X—formerly Twitter—sued Minnesota, calling that state’s version a threat to free speech, according to Reuters.

Advertisers are upgrading too. Meta’s Advantage+ suite lets marketers delegate campaign setup to machine-learning systems that remix headlines and images automatically, a capability Meta showcased in a 2023 newsroom post on its AI-driven ad tools. Google’s Performance Max applies the same logic across Search, YouTube and Maps, as explained in a 2025 update to Google Ads Help. This form of 'tuned advertising' dynamically optimizes ads to users in real time, a process actively studied by researchers and outlined in PolicyReview.info.

Europe’s Digital Services Act, effective since early 2024, empowers EU regulators to demand algorithmic access and independent audits from the largest platforms, as the Commission outlines on its enforcement page. In the United States, transparency still relies on voluntary disclosures and scattered state laws. The potential for consumer manipulation via online behavioral advertising, which tensions with the ideal of consumer autonomy, has largely been overlooked by academia in favor of privacy and discrimination concerns, according to research on arXiv.org.

Patterns Hiding in Plain Sight

Scale plus data is never neutral. Whether the channel is radio, cable news or a "For You" feed, algorithms chase engagement, and emotional extremes—outrage, euphoria, fear—win that contest more often than nuance.

The consent gap widens each year. A single click may satisfy contract law, but meaningful consent requires comprehension and voluntariness—rare commodities inside a 12,000-word terms-of-service scroll.

Fragmented realities flourish. Micro-targeted ads let two neighbors inhabit divergent information worlds, undermining a shared public sphere and complicating collective fact-checking. Furthermore, the ability of generative AI tools to translate text and audio into many languages significantly cuts campaign costs and enables reach to linguistic or ethnic minority voters, impacting diverse democracies, as discussed by LSE Public Policy Review.

AI has driven the cost of convincing fakery toward zero. A decade ago fabricating a realistic hoax video required a studio budget; today a laptop and open-source code suffice. Verification grows laborious just as falsification becomes effortless. The rapid rise of AI chatbots like ChatGPT and their potential for misinformation have sparked considerable debate, prompting concerns about AI's threat to democracy, as highlighted by the Journal of Democracy.

Staying Sane Inside the Test Chamber

Personal vigilance is no silver bullet, but a few habits help. First, diversify the feed: rotate among outlets with transparent editorial standards and lend extra weight to sources that publish corrections. Variety limits any single algorithm’s leverage.

Second, tame the settings. Most major platforms let you mute hyperactive accounts, tighten ad categories or switch to chronological order. None is perfect, yet each layer of friction slows the persuasion treadmill.

Third, practice the 24-hour pause. If a headline spikes your pulse—or your joy meter—wait before sharing. Emotional arousal is the oldest trick in the persuasion playbook; time breaks the spell.

Fourth, push for structural fixes. Independent algorithmic audits, clear labeling of AI-generated media and opt-in data experiments now appear in draft bills from Brussels to Sacramento. Collective pressure—not just personal hygiene—moves policy.

Above all, remember that being online today means living inside a continuous experiment. The algorithms do not "know" you in a soulful sense, but they map your triggers with scientific rigor. Choosing when to play—and when to log off—may be the most consequential act of digital self-defense.

Nearly a century after frightened listeners fled a fictional Martian invasion, the same core question lingers: who controls the frame of reality? Until transparency catches up with engineering, emotional agency will depend on an uneasy alliance—vigilant citizens and smarter policy racing against ever-smarter machines.

Sources

- Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E., and Hancock, J. T. "Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014.

- Segelken, H. R. & Shackford, S. "News feed: 'Emotional contagion' sweeps Facebook." Cornell Chronicle, 10 Jun 2014.

- "Facebook emotional manipulation experiment." Wikipedia entry, last modified 2025.

- Thompson, C. "Orson Welles’ 'War of the Worlds' panic broadcast." Wired, 30 Oct 2008.

- U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. "Social Media Influence in the 2016 U.S. Elections." Hearing, 26 Oct 2017.

- "Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal." Wikipedia entry, last modified 2025.

- Fernández-Abascal, B. F. et al. "TikTok use and adolescent mental health: a systematic review." European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2024.

- Maddison, M. "Musk’s X sues to block Minnesota deep-fake law over free-speech concerns." Reuters, 23 Apr 2025.

- European Commission. "The enforcement framework under the Digital Services Act." 2025.

- Meta. "How AI is powering marketing success and business growth." Newsroom post, 1 Jun 2023.

- Google Ads Help Center. "Optimisation tips for Performance Max campaigns with a Google Merchant Center feed." 2025.

- Federal Trade Commission. "A brief overview of the FTC’s investigative, law-enforcement and rule-making authority." 2025.

- Foos, Florian. "The Use of AI by Election Campaigns." LSE Public Policy Review, 2024.

- Kreps, Sarah and Kriner, Doug. "How AI Threatens Democracy." Journal of Democracy, 2025.

- Zard, Lex. "Consumer Manipulation via Online Behavioral Advertising." arXiv:2401.00205, 2023.

- Internet Policy Review. "Observing 'tuned' advertising on digital platforms." 2024.