Yet the real hero of that breakthrough was not silicon but math first formalized more than four decades earlier: backpropagation of error. By letting networks adjust their internal connections layer by layer, the algorithm cracked the "credit-assignment" puzzle—deciding which weight deserves praise or blame for a wrong answer. Today the same calculus quietly tunes everything from AlphaGo to the photo filters on your phone.

From Toy Neurons to the First Hype Cycle

The dream of machine neurons began in 1943, when Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts proposed a binary firing model that mirrored the all-or-nothing spikes of biological cells. Five years later psychologist Donald Hebb sketched a simple learning rule—"cells that fire together wire together"—hinting that connection weights could store memory. These ideas lit the imaginations of post-war cyberneticians even though hardware was still vacuum-tube-sized.

By 1958, Cornell's Frank Rosenblatt unveiled the Mark I Perceptron aboard a U.S. Navy research ship. Headlines trumpeted a machine that could "walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence." In reality the single-layer perceptron was a linear classifier: powerful for linearly separable tasks but blind to an XOR gate's simple twist.

That shortcoming became fatal when Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert's 1969 book Perceptrons mathematically proved the limits of one-layer models. Funding evaporated, ushering in an "AI winter" whose chill lasted into the Reagan years. The field needed not just more layers but a principled way to teach them.

More Technology Articles

The Credit-Assignment Conundrum

Imagine a freshman group project that bombs. Without individual feedback, no student knows who should fix what. Early multilayer networks suffered the same fate: only the final layer saw the teacher's red ink. Error signals had to be divvied up so each hidden weight could nudge itself in the right direction. Researchers tried random perturbations and exhaustive finite-difference checks, but the math scaled worse than all-night debugging sessions.

Early Mathematical Roots

Long before the deep-learning boom, Finnish computer scientist Seppo Linnainmaa introduced the reverse mode of automatic differentiation in his 1970 master's thesis, providing an efficient way to compute gradients through a chain of operations. American researcher Paul Werbos outlined the idea in his 1974 Harvard dissertation and later published the first neural-network-specific application in 1982, popularizing the term "backpropagation." Their work circulated quietly until faster computers and larger datasets arrived a decade later.

When Errors Finally Flowed Backward

Popular recognition came in 1986, when David Rumelhart, Geoffrey Hinton and Ronald Williams published "Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors" in Nature. Borrowing the chain rule from freshman calculus, they showed how to shuttle gradients from the output toward the input, layer by layer, at a computational cost only twice the forward pass. Suddenly networks could tackle XOR, handwritten digits—even toy speech tasks—without brute-force guesswork.

Google Scholar lists just over 40,000 citations for that Nature paper as of 2025—staggering, though still shy of the DNA double-helix landmark—and more than 55,000 for the expanded chapter in the team's two-volume Parallel Distributed Processing book. But citations don't pay GPU bills, and 1980s hardware was too feeble to train anything deeper than a few hidden layers.

Demystifying the Math

Every neural network learns in two acts: a forward pass and a backward pass.

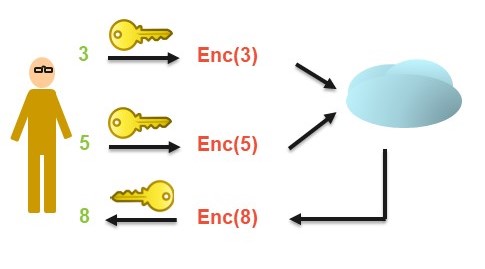

In the forward pass, data flows through layers of artificial neurons, each connection—or weight—nudging the signal slightly before it reaches the output. The model then measures how far its prediction missed the mark using a loss function: cross-entropy for choosing between categories, mean-squared error for continuous values.

The backward pass is where the learning begins. The network asks, which connections caused the mistake? Using the chain rule from calculus, it traces how much each neuron’s output contributed to the final error. Every neuron receives a tiny feedback signal—its delta (δ)—showing how responsible it was. These deltas ripple backward through the network, letting each weight calculate how much to adjust itself.

Once those gradients are known, the network updates its parameters through stochastic gradient descent—a method that moves each weight a small step downhill on the loss curve. The rule is simple:

wnew = wold − η·∂L⁄∂w

where η (eta) is the learning rate, deciding how big each step should be.

Modern optimizers like Adam add refinements—momentum, adaptive step sizes—but the logic remains identical: take small, smart steps until the landscape flattens.

A simple XOR demo captures the idea. With just two hidden neurons, a tiny network can learn to output 1 only when its inputs differ. Starting from random guesses, it figures this out in under a thousand training rounds on a laptop. The same principle now scales to billion-parameter language models because the math is local: each layer talks only to its neighbors. That locality makes the calculus of a toy network the same one that trains GPT.

Why Backprop Slept for Two Decades

Early PCs choked on floating-point matrix math, and sigmoid activations squashed gradients toward zero—an effect Yann LeCun later called the "vanishing-gradient problem." Meanwhile, statistical methods such as support-vector machines scored academic wins with less compute. Backprop was a teenage prodigy stuck waiting for the world to catch up.

Even as late as 2005, training a modest speech recognizer could take weeks on CPU clusters. The algorithm's elegance was never in doubt, but practical payoff required a hardware boost and oceans of labeled data.

Silicon Meets Data

Enter NVIDIA's 2006 release of CUDA, a programming model that turned gaming GPUs into general-purpose parallel engines. Backprop's matrix multiplies mapped perfectly onto thousands of GPU cores. Krizhevsky's AlexNet leveraged that power in 2012, lowering ImageNet top-5 error to 15.3 percent and later earning the paper a NeurIPS 2022 Test of Time award.

Cloud giants soon offered rentable GPU clusters, while open-source frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow democratized experimentation. A freshman can now spin up a ResNet on Colab in minutes—proof that algorithms, hardware and data advance as a three-legged race.

Backprop Everywhere

Computer vision reaped early rewards: residual networks, diffusion models for image synthesis and real-time pose estimation. Speech followed with WaveNet, producing human-like voices by chaining gradients through 30-layer stacks. Reinforcement learning added policy gradients to beat Atari and Go, all while relying on the same backward calculus.

Language models pushed scale into the stratosphere. Transformers like GPT-4 route gradients across sparse attention blocks—software tricks that skip unnecessary calculations and slash cost. Every autocomplete keystroke you enjoy today owes a debt to the 1970s reverse-mode insight and the 1986 chain-rule revival.

Pushback, Power Bills — and Gradient-Free Experiments

Critics argue that backprop is biologically implausible—neurons don't pass signed error signals in reverse—and environmentally costly. A Stanford-led analysis estimates that training GPT-4 may have consumed roughly 50 gigawatt-hours of electricity, enough to power San Francisco for about three days. Exact figures remain opaque because OpenAI and its cloud partners keep detailed logs confidential.

Researchers are now probing three fronts: Speed-ups that keep gradients but trim compute. "Highway Backpropagation," a 2025 preprint, iteratively accumulates gradient estimates along residual paths so layers can backpropagate in parallel. Experiments on ResNets and Transformers show multi-fold speed-ups with minimal accuracy loss. Forward-only or local-learning rules. "Forward Target Propagation" replaces the backward pass with a second forward sweep, delivering backprop-level accuracy on CIFAR-10 while avoiding weight-symmetry constraints and slashing energy use—an attractive match for neuromorphic chips. Re-ordering the training loop itself, with some studies finding that processing mini-batches in reverse order can stabilize convergence and improve generalization.

Hardware labs are exploring radical shifts, too. Physicists recently demonstrated end-to-end optical backpropagation: saturable-absorber layers let light itself carry error signals backward through an analog neural network, pointing toward ultra-low-power training rigs. Meanwhile, reversible-computing advocates note that running logic gates backward can, in principle, avoid the heat dissipation mandated by fundamental thermodynamic limits.

What Comes After Backprop?

Scaling laws still reward bigger models, but diminishing returns loom. Mixture-of-experts layers, adaptive sparsity and low-rank adapters aim to keep gradients flowing while trimming energy bills. Hardware is shifting too: wafer-scale engines, optical matrix multipliers and memristive arrays promise analog speed-ups that could make yesterday's GPU gains look quaint.

If a true successor emerges, it will likely graft onto backprop rather than replace it—just as an electric car still relies on wheels and axles. For now, the algorithm remains the lingua franca of machine learning, its derivatives quietly steering billions of model updates each second.

Backprop's 50-year journey from theory to ubiquity reminds us that breakthroughs seldom explode overnight. They percolate in dissertations, wait for silicon and finally surface when the world catches up. The next time your phone translates a menu or sketches an image from a prompt, remember the humble chain rule pulsing beneath—still teaching machines to learn backwards so the future can move forward.

Sources

- Linnainmaa, S. "Taylor Expansion of the Accumulated Rounding Error." BIT Numerical Mathematics, 1970.

- Werbos, P.J. Beyond Regression: New Tools for Prediction and Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences. Harvard University Ph.D. dissertation, 1974.

- Rumelhart, D.E., Hinton, G.E., & Williams, R.J. "Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors." Nature, 1986.

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G.E. "ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks." NIPS 2012.

- Fagnou, E. et al. "Accelerated Training through Iterative Gradient Propagation Along the Residual Path (Highway-BP)." arXiv:2501.17086, 2025.

- Saadat As-Saquib, N. et al. "Forward Target Propagation." arXiv:2506.11030, 2025.

- Pai, S. et al. "Experimentally realized in situ backpropagation for deep learning in photonic neural networks." Science, 2023.

- Spall, J., Guo, X., & Lvovsky, A.I. "Training neural networks with end-to-end optical backpropagation." Advanced Photonics, 2025.