One day later, the Bootstrap board released a public letter titled "We Are All Zashi" stating that it had confronted proposals to attract outside investment and privatize the Zashi wallet while working with counsel. The board explained that its 501(c)(3) obligations left it with limited flexibility over how charitable assets and intellectual property could be moved or monetized, as detailed on We Are All Zashi.

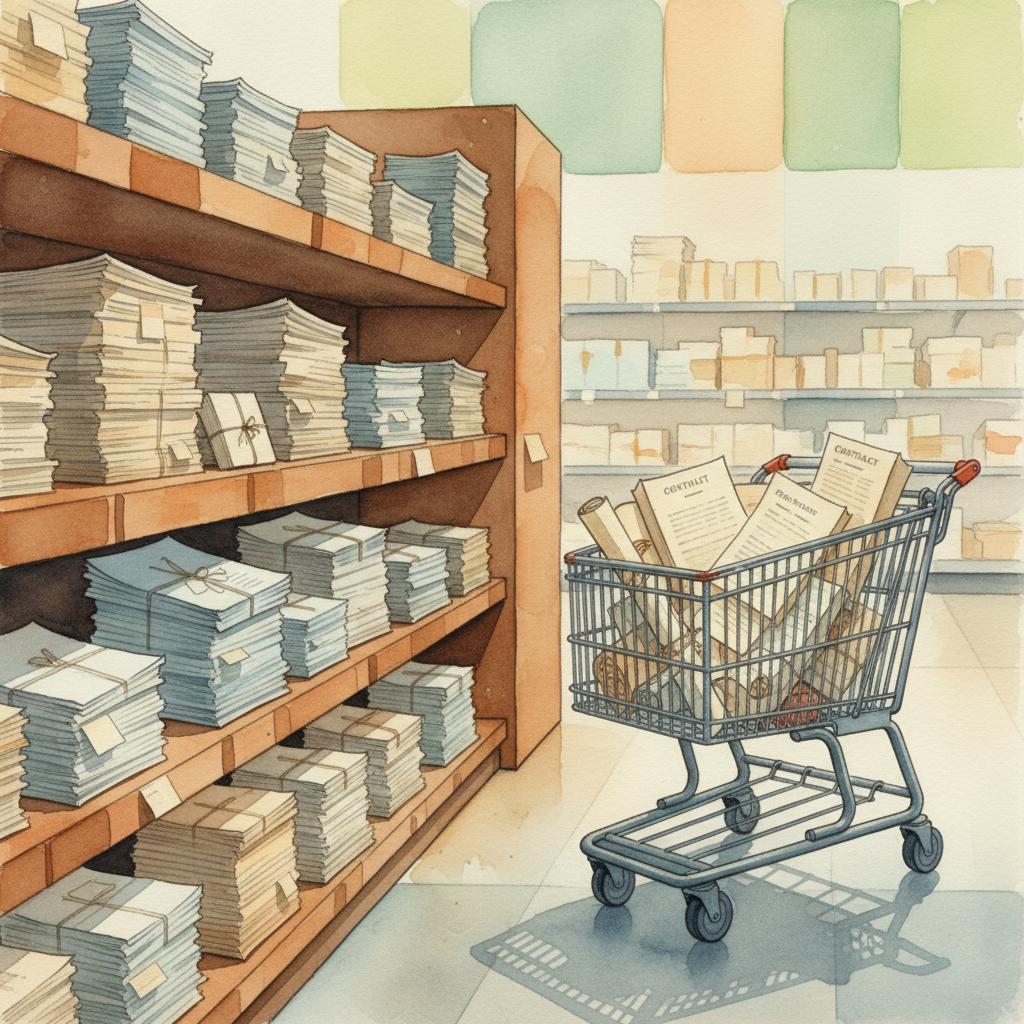

The clash in the Zcash ecosystem arrives as other high-profile nonprofits, most notably OpenAI, have adopted hybrid structures to raise large amounts of capital under continued nonprofit oversight. This builds on the legal framework for 501(c)(3) entities described in Beige Media’s earlier analysis of exemption rules and tradeoffs.

Key Takeaways

- Section 501(c)(3) requires organizations to pursue exempt purposes and bars any net earnings from inuring to private insiders.

- Unrelated business income tax applies to commercial activity not substantially related to mission, often steering major ventures into taxable subsidiaries.

- Bootstrap’s handling of proposed Zashi wallet privatization shows how nonprofit fiduciary duties can collide with venture-style investment plans.

- The resignation of Electric Coin Company’s team and launch of a new wallet entity highlight governance risk when key IP sits inside a charity.

- OpenAI’s capped-profit LP and later public benefit corporation structure offer one model for raising capital while keeping nonprofit control.

How 501(c)(3) Law Treats Revenue and Private Benefit

Under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3), an organization must be organized and operated exclusively for exempt purposes such as charitable, educational, or scientific work. Furthermore, no part of its net earnings may inure to the benefit of a private shareholder or individual, according to guidance from the Internal Revenue Service.

Private inurement rules focus on insiders such as founders, directors, and key employees, who may receive only reasonable compensation for services. The broader private benefit doctrine limits arrangements that confer more than incidental advantage on specific private parties, as summarized in Beige Media’s review of exemption requirements.

Revenue-generating activity is permitted, but when a tax-exempt organization regularly carries on a trade or business that is not substantially related to its exempt purpose, net income from that activity is subject to unrelated business income tax, or UBIT. This may require filing Form 990-T, as outlined in IRS materials on unrelated business income tax.

UBIT is primarily a tax mechanism rather than an automatic revocation trigger. Yet persistent emphasis on unrelated commercial operations can raise questions about whether the organization is still operated for exempt purposes. This is why many charities route substantial business ventures through separate taxable subsidiaries rather than running them directly.

An IRS training paper on for-profit subsidiaries notes that a separately incorporated taxable subsidiary is generally treated as distinct from its exempt parent, so long as the subsidiary has a real business function and is not merely an instrumentality. Most income the parent receives in the form of dividends, royalties, or certain rents can be excluded from UBIT if statutory conditions are met.

At the same time, that IRS guidance stresses that transactions between the exempt parent and the subsidiary must occur on an arm’s-length basis. A parent–subsidiary structure cannot serve as a shield against inurement, because excessive payments, below-market transfers of assets, or other non-market terms can still be treated as impermissible private benefit.

More Business Articles

Bootstrap, Zashi and the Boundaries of a 501(c)(3)

Bootstrap is described on Zcash’s own ecosystem site as a nonprofit public charity under section 501(c)(3) that owns Electric Coin Company and supports the Zcash ecosystem. This situates the core protocol and the Zashi wallet within a charitable governance structure, according to Zcash materials.

In 2020, ECC shareholders voted to donate 100 percent of their shares to Bootstrap, making ECC a wholly owned subsidiary of the nonprofit. This consolidated control over development of the Zcash protocol and related software inside the charity, as described in a company announcement on the Zcash site.

The Zashi mobile wallet, promoted within the ecosystem as a self-custody Zcash-only wallet with shielded transactions, became a focal point for proposals to bring in external capital. The idea involved shifting some rights into a new private vehicle, a move that Bootstrap’s board said it evaluated with legal counsel while trying to remain consistent with U.S. nonprofit law and the long-term mission of Zcash, according to its statement on We Are All Zashi.

“Bootstrap/ECC's nonprofit constraints are real, and navigating them responsibly can be complex particularly in a changing environment.”

In the same statement, the board warned that the last version of the proposed Zashi transaction could expose Bootstrap to donor lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny, or even an unwinding in which the asset would have to be transferred back. It argued that these risks extended beyond the immediate parties and could affect the broader Zcash ecosystem.Reporting on the dispute explains that discussion of external investment and “alternative structures” to privatize Zashi was a central fault line. Bootstrap presented its objections as rooted in nonprofit law around how charitable assets and intellectual property can be structured in deals that benefit private investors.

ECC’s Exit and a New Wallet Built on Zashi

“Yesterday, the entire ECC team left after being constructively discharged by ZCAM. In short, the terms of our employment were changed in ways that made it impossible for us to perform our duties effectively and with integrity.”

That description, posted by Josh Swihart and cited in coverage by The Block, framed the January 7 resignations as a response to governance changes by the nonprofit’s board rather than a loss of faith in the Zcash protocol itself.“Importantly, the Zcash protocol is unaffected. This decision is simply about protecting our team’s work from malicious governance actions that have made it impossible to honor ECC's original mission.”

Swihart emphasized in comments reported in Coindesk’s coverage that the protocol remains operational and open-source. The team’s concern centered on what it described as harmful governance actions, rather than technical flaws or a decision to abandon privacy-focused development.Following the departure, the former ECC developers announced plans for a new company and unveiled "cashZ," a new Zcash wallet built on the Zashi codebase. This signaled an intention to continue building wallet software outside Bootstrap’s corporate structure while relying on code originally developed under the nonprofit umbrella.

Bootstrap’s board, for its part, expressed respect for the departing team’s contributions but framed the split as a disagreement about compliance with the legal and fiduciary obligations of a 501(c)(3) charity. It was characterized as a dispute over legal structure rather than a dispute over Zcash’s mission or the abstract merits of for-profit investment.

Legal Pressure Points in the Zashi Dispute

The Zashi proposals sat at the intersection of several IRS doctrines: the prohibition on private inurement for insiders, limits on private benefit to investors or acquirers, and rules governing when income from controlled subsidiaries or licensing arrangements becomes unrelated business taxable income.

If a charity were to transfer a valuable software asset such as a widely used wallet into a privately owned company at less than fair market value, regulators could view the deal as conferring impermissible private benefit or inurement. This risk remains even if the asset continues to serve users, should the terms effectively shift future upside to a narrow group of investors or employees.

Bootstrap’s statement highlighted exactly these concerns, noting that donors could challenge a flawed transaction and that regulators might scrutinize valuation and process. It also warned that an unwinding could be ordered, which would return Zashi to ECC and disrupt any investors that had relied on the new structure.

IRS guidance on controlled organizations and for-profit subsidiaries underscores why Bootstrap framed the issue in this way. The more a tax-exempt parent appears to treat a subsidiary or related entity as an instrumentality, or enters into non-arm’s-length transactions, the more likely it is that income flows and asset transfers will be recharacterized as unrelated business income or inurement.

From the ECC side, public statements portrayed the dispute as a case of misaligned governance by specific Bootstrap directors that made it impossible to carry out the team’s work. Strong language about malicious governance was paired with continued commitment to Zcash as a protocol, placing legal structure rather than technical or ideological disagreement at the center of the rupture.

Viewed through the 501(c)(3) lens, the episode shows how a board may prioritize strict compliance with charitable asset rules, even at the cost of losing its entire development team. Meanwhile, developers may judge the same constraints as intolerable when they prevent pursuit of a venture-backed roadmap for products like a mobile wallet.

OpenAI’s Capped-Profit and PBC Path

OpenAI offers a contrasting example of how a research nonprofit has tried to structure for-profit activity within, and then adjacent to, a 501(c)(3) framework while retaining nonprofit control and emphasizing public mission, according to the organization’s company communications on OpenAI.

Founded in 2015 as a nonprofit with a mission to ensure artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity, OpenAI created a for-profit subsidiary in 2019. This entity, OpenAI LP, was described in a company blog post as a "capped-profit" structure that allowed investors and employees to receive capped returns while any value beyond the cap would accrue to the original OpenAI nonprofit.

That post explained that OpenAI LP remained controlled by the nonprofit’s board and that the nonprofit’s charter obligations came before financial returns in fiduciary terms. Only a minority of board members could hold economic stakes, which together were intended to keep the entity focused on mission while still attracting capital and staff with equity-like upside.

In 2025, OpenAI announced that it was updating this arrangement by converting the for-profit arm into a public benefit corporation called OpenAI Group PBC. The nonprofit parent was renamed OpenAI Foundation and retained governance control and a large equity stake, as described in its structural overview.

The organization’s explanation stressed that the Foundation appoints and can replace all directors of the PBC and holds a 26 percent equity stake plus a warrant tied to long-term valuation. The recapitalization process involved extended dialogue with the attorneys general of California and Delaware, who oversee aspects of nonprofit law in those jurisdictions.

This trajectory, from a nonprofit to a capped-profit subsidiary and then to a PBC under nonprofit control, illustrates one way to place high-growth, capital-intensive activity in a conventional corporate wrapper. It demonstrates an effort to anchor control and much of the financial upside in a 501(c)(3) entity focused on broad public benefit.

Designing For-Profit Initiatives Without Losing 501(c)(3) Status

The Zcash and OpenAI cases highlight a toolkit that nonprofit boards and counsel often rely on when they seek to pursue commercial opportunities. This includes licensing intellectual property instead of transferring ownership, setting up taxable subsidiaries for unrelated business lines, entering joint ventures with clear mission covenants, and using cost-sharing or royalty agreements to keep value flowing back to the charity.

IRS technical materials on for-profit subsidiaries point out that when a subsidiary is genuinely separate, its commercial operations do not generally jeopardize the parent’s exempt status. Dividends and some other payments to the parent can be excluded from UBIT, but they also stress that control tests and debt-financing rules can bring those income streams back into the tax base if transactions are not structured carefully.

For boards, this means that valuation methods, independent advice, conflict-of-interest policies, and clear records of arm’s-length negotiation are not simply governance best practices. They are pieces of evidence that regulators, donors, or courts may examine if a major transaction appears to shift charitable assets or opportunities to private investors or staff.

State attorneys general play an important role in this space, particularly for large, high-visibility entities. OpenAI’s account of months of engagement with the California and Delaware attorneys general before finalizing its recapitalization shows that major restructurings can draw direct oversight even when they keep a nonprofit parent in formal control.

In smaller or emerging projects such as Zcash’s Bootstrap, that scrutiny may instead come through the risk of donor litigation, community backlash, or future IRS examination. This can make boards especially conservative when weighing any proposal that appears to move core mission assets like a flagship wallet into private hands.

Ultimately, the choice is not between being "nonprofit" or "for-profit" in a binary sense. It is about how to align structures so that capital, talent, and governance all reinforce the public-benefit commitments that justified 501(c)(3) status in the first place.

What Zcash and OpenAI Signal for Future Hybrids

The Zashi dispute underscores how quickly tensions can escalate when a charity’s board views proposed deals as incompatible with its legal duties. Meanwhile, the development team sees those same constraints as an obstacle to executing a product and investment strategy, even when both sides say they share the same mission.

OpenAI’s path, by contrast, shows how early and explicit attention to structure can channel large-scale capital into a mission-driven project without abandoning formal nonprofit oversight. This includes caps on returns, reserved governance powers for the nonprofit, and later a shift into a public benefit corporation, even if the model remains subject to public debate.

As more 501(c)(3) organizations develop valuable software, data, and brands, boards and founders will increasingly face choices similar to those in Zcash and OpenAI. They must decide whether to keep assets inside a charity and accept slower, more constrained growth or to adopt hybrid structures that invite both investment and legal scrutiny over how public and private interests are balanced.

The law does not prevent nonprofits from pursuing revenue, partnerships, or even ambitious commercial ventures. But it does insist that any such effort be structured so that mission, not private gain, remains the governing principle. This standard will continue to shape how hybrid nonprofit–for-profit models evolve in the years ahead.

Sources

- Beige Media. "501(c)(3) vs. For-Profit: The Structural Difference." Beige Media, 2026.

- Internal Revenue Service. "Inurement/private benefit: Charitable organizations." Internal Revenue Service, 2025.

- Internal Revenue Service. "Unrelated business income tax." Internal Revenue Service, 2025.

- Internal Revenue Service. "E. For-Profit Subsidiaries of Tax-Exempt Organizations." Internal Revenue Service, n.d..

- Zcash. "Bootstrap." Electric Coin Company, 2023.

- Electric Coin Company. "ECC owners approve donation to Bootstrap Project." Electric Coin Company, 2020.

- Bootstrap Board. "We Are All Zashi." Bootstrap, 2026.

- Brian Danga. "Zcash developers quit, form new company after board clash." The Block, 2026.

- CoinDesk Staff. "Zcash governance clash tanked the ZEC token. Here's why it may not be as big as it seems." CoinDesk, 2026.

- OpenAI. "Our structure." OpenAI, 2025.

- Greg Brockman, Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI. "OpenAI LP." OpenAI, 2019.