In 2024, the European Union adopted the Artificial Intelligence Act, which sets binding requirements for "high-risk" AI systems. Article 10 requires training, validation, and testing datasets to follow explicit data governance practices. These datasets must be relevant, sufficiently representative, and, as far as possible, free of errors and complete for the intended purpose.

Article 15 requires high-risk systems to achieve appropriate levels of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. They must also perform consistently over their lifecycle, with declared accuracy metrics in the instructions for use, according to the consolidated text hosted by the AI Act Service Desk.

Together, these frameworks signal a shift in how institutional AI is expected to operate. Large models cannot be treated as experimental autocomplete tools when used in public benefits, defense, finance, healthcare, or Building Information Modeling (BIM). They must be governed as safety-relevant data systems whose value depends on data integrity, accurate outputs, and traceable processes supported by technical and organizational controls.

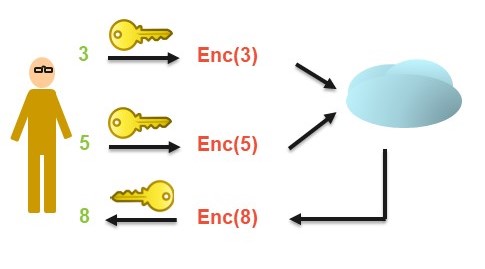

Enterprise practice is beginning to reflect this orientation. One recent enterprise blog from Centroid notes that simply redacting sensitive information before sending it to generative models can degrade results or prompt fabricated content.

This underscores that protecting confidential data and preserving useful context must be handled together. That operational concern aligns with the formal guidance emerging from public bodies on data quality, documentation, and risk management for institutional AI.

Key Governance Requirements for Institutional AI

- NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework links trustworthy AI to continuous testing, measurement, and documentation of validity and reliability across the system lifecycle.

- The EU AI Act requires high-risk systems to use governed datasets and document appropriate levels of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity, with declared accuracy metrics.

- AI in public services, social protection, and defense raises accountability and safety concerns that make high-quality data, evaluation, and human oversight mandatory, not optional.

- Financial regulators and standard setters stress model risk management, data quality, and third-party dependencies as central AI governance challenges.

- Healthcare, construction, and BIM research highlights that incomplete, biased, or poorly governed data can turn AI outputs into direct safety, liability, and trust risks.

From Principles to Practice: Core Governance Frameworks

NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework positions risk management as a continuous process covering governance, mapping, measurement, and management functions. In the framework, trustworthy AI systems are expected to be valid and reliable, safe, secure and resilient, accountable and transparent, explainable and interpretable, privacy-enhanced, and fair, with harmful biases managed. These properties are to be supported by systematic test, evaluation, verification, and validation activities throughout the lifecycle, as outlined in the AI RMF description on NIST.

The AI RMF stresses that measurement in controlled environments is not enough. It notes that risks can differ markedly once systems move into operational contexts. Organizations need mechanisms to track emergent risks, document residual risk, and integrate AI risk management into broader enterprise risk practices. That includes accounting for third-party data, models, and infrastructure whose risk metrics may not align with internal standards. It also means recognizing that inscrutable systems make risk measurement and accountability more difficult.

Data quality appears repeatedly across these recommendations. The framework highlights that biased, incomplete, outdated, or otherwise poor-quality data can undermine validity and trustworthiness, even when algorithmic techniques are sound. That framing matches the growing consensus that institutional AI governance must focus at least as much on data curation, lineage, and monitoring as on the choice of model architecture or parameter scale.

The EU AI Act translates many of these principles into law for high-risk systems. Article 10 requires providers to apply data governance and management practices appropriate to the intended purpose. This includes design choices, data collection processes and origins, documentation of preprocessing operations, and explicit assumptions about what the data represent.

It also requires assessments of data availability and suitability, examination for biases likely to affect health, safety, or fundamental rights, and measures to detect, prevent, and mitigate such biases, according to the consolidated Article 10 text published by Artificial-Intelligence-Act.com.

Article 15 complements this by requiring that high-risk systems be designed to achieve an appropriate level of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. Providers must declare accuracy levels and relevant metrics, and systems must be resilient to errors, faults, and adversarial attempts to manipulate training data, models, or inputs, as summarized in the Article 15 explanation on AI-Act-Law.eu.

These governance frameworks set a baseline expectation: in institutional contexts, accuracy, robustness, and data integrity are lifecycle obligations, not one-time checks. They also shift documentation from internal practice to a requirement that directly shapes how systems are specified, procured, audited, and contested.

More Technology Articles

Public Services, Eligibility, and Digital Inclusion

Governments now apply AI across public service design and delivery. According to an issue overview on public services from OECD.AI, administrations use AI for 24/7 citizen support via chatbots, tailored responses to inquiries, and proactive service delivery that can include automatic eligibility checks for benefits. These systems promise faster responses and more consistent application of rules.

More detailed OECD work on governing with AI in core government functions describes how linking administrative datasets enables governments to streamline benefit applications, support automatic pre-filling of forms, and in some cases automatically enroll eligible citizens in social programs. This kind of proactive social protection relies heavily on accurate linkage, up-to-date records, and clear eligibility logic translated into deterministic or data-driven models.

The same reports warn that data infrastructure, staff capacity, and evaluation practices often lag behind ambitions. When eligibility decisions depend on incomplete or fragmented records, errors can lead to wrongful denials, delayed support, or uneven treatment across groups.

If AI models draw on biased or unrepresentative data, they can reproduce existing exclusion patterns or overlook people who interact less with digital channels.

From a governance perspective, this means that data quality checks, documentation of training and rule sets, and ongoing monitoring of outcomes are central to using AI in public services. Accuracy is not only a statistical goal but also a condition for legal defensibility when individuals challenge decisions, and for maintaining public trust in digital government channels.

Defense and Mission-Critical Decision Support

Defense organizations have identified AI as strategically important but also risk-sensitive. An overview course guidebook from the U.S. Defense Acquisition University describes how the Department of Defense is building capacity to acquire AI-enabled systems while addressing responsible AI principles, ethics, and an evolving AI and data policy landscape, as summarized in the SWE0058 course description on DAU.

The U.S. Army’s AI Layered Defense Framework, outlined in a public request for information, proposes a structured, multi-layered approach to AI risk. It emphasizes measurable requirements, testing, and evaluation regimes aligned with mission needs. The framework treats robustness against adversarial manipulation, system monitoring, and clear performance baselines as prerequisites for using AI in operational workflows, according to the RFI instructions published by the U.S. Army.

These documents reflect a basic reality of defense AI: decision support systems that misclassify targets, misinterpret sensor data, or fail under adversarial conditions can have direct operational consequences.

As a result, defense guidance places particular weight on test, evaluation, verification, and validation across representative conditions. It also emphasizes understanding how models behave when confronted with deceptive inputs or data drift.

In this context, the institutional AI governance problems are not abstract. Data provenance, scenario coverage in testing, and the integrity of pipelines that feed models become central to mission assurance. The frameworks developed for AI acquisition and layered defense are early examples of sector-specific governance that treats AI as safety-relevant infrastructure embedded in complex socio-technical systems.

Financial Services, Model Risk, and Systemic Stability

Financial institutions have been early adopters of AI for trading, credit decisions, fraud detection, and customer service. A 2025 report on artificial intelligence in financial services from the U.S. Government Accountability Office notes that banks and other firms use AI for automated trading, credit underwriting, customer support, and risk management. These applications deliver efficiency gains but also introduce new risks related to biased lending, data quality, privacy, and cybersecurity, as described by GAO.

The same report highlights that federal financial regulators largely rely on existing laws, regulations, and risk-based examinations to oversee AI. However, it identifies gaps in model risk management guidance, particularly for credit unions that depend on third-party technology providers.

Without detailed guidance on how to manage AI model risk, institutions may underestimate the consequences of data drift, opaque model behavior, and reliance on external vendors.

At the system level, a 2024 report from the Financial Stability Board assesses how broader AI adoption could affect financial stability. The FSB notes that AI offers benefits in operational efficiency, regulatory compliance, and product personalization. However, it may also amplify vulnerabilities through third-party dependencies, correlated model behavior across institutions, cyber risks, and weak data governance, according to the overview of AI-related vulnerabilities published by the FSB.

The U.S. Treasury’s 2024 report on AI in financial services, summarized in a press release from the Treasury Department, similarly underscores that AI, including generative models, can broaden access and improve monitoring for illicit finance. It also highlights heightened concerns around data privacy, bias in credit decisions, and concentration in third-party service providers. It recommends continued monitoring, coordination among regulators, and attention to how data and vendors shape the risk profile of AI applications.

These findings converge on a common theme: in finance, AI governance is inseparable from model risk management and data controls. Institutions need to know where their data comes from, how often models are recalibrated, and how performance is monitored across different market conditions. They also need to know how to audit and explain decisions that affect consumers and counterparties. Without that, AI can introduce opaque sources of credit, market, and operational risk.

Healthcare, Patient Safety, and Over-Reliance on AI

Healthcare organizations are also embedding AI into diagnostic support, imaging analysis, triage, and operational planning. An intelligence briefing from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Sector Cybersecurity Coordination Center describes AI as a tool with significant promise for improving outcomes and reducing costs.

However, it emphasizes that AI and machine learning also introduce cybersecurity, privacy, and data integrity challenges in clinical environments, as detailed in the 2020 HC3 report hosted by HHS. Those challenges include the risk that compromised or manipulated data could feed into clinical decision-support systems. They also include the difficulty for clinicians to interpret model behavior, and the expanded attack surface from connectivity between medical devices and hospital networks.

The report underlines the need for secure architectures, vendor due diligence, and clear policies on data use and model updates in healthcare settings.

Beyond security, recent experimental work on medical AI highlights the risk of over-reliance on systems that are not fully accurate. A 2025 paper on the "AI Transparency Paradox" finds that providing explanations for medical AI recommendations can increase diagnostic accuracy when the AI is correct.

However, it systematically reduces accuracy when the AI is wrong, because explanations make clinicians more likely to accept both correct and incorrect advice, according to Khanna and coauthors’ study published via Chapman University.

For institutional AI governance in healthcare, this suggests that transparency and explainability are not substitutes for accuracy and robust validation. Models must be evaluated on clinically relevant datasets, monitored after deployment, and integrated into workflows that preserve the ability of clinicians to question or override AI outputs. This approach prevents blind trust in the presence of persuasive explanations.

Construction, BIM, and the Built Environment

Construction has begun to adopt AI for activity monitoring, risk prediction, scheduling, and quality control, but it remains one of the least digitized sectors. A comprehensive review of AI in the construction industry published in the Journal of Building Engineering notes that despite potential benefits in cost, safety, and productivity, adoption is hampered by cultural barriers, high initial costs, security and trust concerns, and shortages of digital skills, according to Abioye and coauthors’ 2021 study archived by Brunel University.

The same review highlights that AI applications in construction draw on diverse techniques, from computer vision for safety monitoring to machine learning for cost estimation and logistics. In each case, the quality and completeness of project data, and the integration with existing project management systems, strongly influence whether AI can deliver reliable insights rather than inconsistent or misleading recommendations.

As large language models enter construction workflows, new governance questions arise. A 2025 comparative study of large language models for construction risk classification finds that transformer-based models such as GPT-4, when prompted appropriately, can classify textual risk items into categories with performance approaching that of the best traditional models, without additional training data, according to results published in Buildings and shared via Michigan Technological University.

Those findings suggest that text-based project records, incident reports, and contracts can be mined more efficiently for risk information. However, they also mean that any systematic issues in those records, such as incomplete documentation or biased categorization, will flow directly into the model’s outputs.

Governance therefore needs to include curation of unstructured data sources, clear versioning of prompts and configurations, and evaluation procedures that reflect real project risks rather than only benchmark datasets.

BIM intensifies these stakes because it ties digital information directly to physical assets. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis on BIM in risk management for sustainable bridge projects finds that BIM is used to identify, analyze, mitigate, and monitor technical, financial, environmental, and operational risks across the project lifecycle.

Integrating cost, schedule, and performance data into common data environments improves auditability by linking design intent, construction records, and operational metrics, as reported by Rehman in the Journal of Sustainable Development and Policy and made available by the JSaDP.

When generative AI is layered onto BIM environments to draft specifications, summarize submittals, reconcile as-built models, or answer "what changed" queries, a confident but incorrect output can translate into rework, safety exposure, or contractual disputes.

In that setting, provenance, access controls, and traceability of changes are not optional features. They are core mechanisms that allow project teams, owners, and regulators to reconstruct how data flowed into decisions and to assign responsibility when outcomes diverge from design intent.

Cross-Sector Governance Priorities

Across these sectors, several governance imperatives recur. First, continuous testing and monitoring in real-world conditions are necessary to ensure that accuracy and robustness metrics remain meaningful over time.

Frameworks like NIST’s AI RMF and the EU AI Act’s high-risk provisions both stress that risk management is an ongoing process. It must track emergent risks, document residual risk, and adjust controls as systems and environments change.

Second, data governance is central to trustworthy institutional AI. The EU AI Act’s Article 10 provisions on data relevance, representativeness, and error control codify expectations that many sectors are already struggling to meet in practice.

Public-service, financial, healthcare, and construction case studies all show that biased, stale, or incomplete data can undermine even well-designed models. This leads to outcomes that are difficult to justify or remediate.

Third, documentation and auditability are becoming structural requirements rather than internal preferences. Whether in social protection systems that automatically enroll beneficiaries, credit models that shape lending decisions, or BIM workflows that coordinate complex infrastructure, institutions increasingly need records of what data were used, how models were configured, what accuracy metrics were achieved in which contexts, and how human decision-makers interacted with AI outputs.

Finally, sector-specific risk management practices remain essential. Financial regulators emphasize model risk, third-party dependencies, and systemic implications. Defense organizations highlight adversarial environments and mission-critical reliability.

Healthcare bodies focus on patient safety, cybersecurity, and human factors. Construction and BIM research concentrates on lifecycle risk, interoperability, and asset performance.

Institutional AI governance must reflect these differences while aligning with cross-cutting principles on data quality, transparency, and accountability.

Conclusion: Treating Institutional AI as Safety-Critical Data Infrastructure

The emerging guidance from standards bodies, legislators, regulators, and sector-specific research points in a consistent direction. Institutional AI cannot safely operate as a loosely governed overlay on existing data systems. It must be managed as part of safety-critical data infrastructure, with clear expectations about the quality, provenance, and ongoing supervision of the data and models that drive decisions.

For public agencies, financial institutions, healthcare providers, defense organizations, and construction firms working with BIM, the payoff from AI depends on whether they can prove that systems are accurate enough for their purposes, robust under realistic conditions, and anchored in governed data.

That is a technical and organizational challenge. The direction of travel is clear: trustworthy institutional AI will be defined less by impressive demonstrations and more by the rigor of its data safety, accuracy, and integrity controls.

Sources

- Tabassi, E. "Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0)." National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023.

- European Union. "Artificial Intelligence Act, Article 10: Data and Data Governance." European Union, 2024.

- European Union. "Artificial Intelligence Act, Article 15: Accuracy, Robustness and Cybersecurity." European Union, 2024.

- OECD. "AI in Government: Issues – Public services." OECD, 2025.

- OECD. "Governing with Artificial Intelligence: The State of Play and Way Forward in Core Government Functions." OECD Publishing, 2025.

- Defense Acquisition University. "SWE0058 – Overview of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the DoD Course Guidebook." Defense Acquisition University, 2024.

- Department of the Army. "AI Layered Defense Framework – Request for Information Instructions." U.S. Army, 2024.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. "Artificial Intelligence: Use and Oversight in Financial Services (GAO-25-107197)." U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2025.

- Financial Stability Board. "The Financial Stability Implications of Artificial Intelligence." Financial Stability Board, 2024.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. "Artificial Intelligence in Financial Services: Uses, Opportunities, and Risks." U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2024.

- Health Sector Cybersecurity Coordination Center (HC3). "AI Application and Security Implications in the Healthcare Industry." U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020.

- Khanna, M.; Wang, Z.; Wei, L.; Xue, L. "AI Transparency Paradox: When Medical AI Explanations Help and When They Harm." Chapman University Economic Science Institute, 2025.

- Abioye, S. O.; Oyedele, L. O.; Akanbi, L.; et al. "Artificial Intelligence in the Construction Industry: A Review of Present Status, Opportunities and Future Challenges." Journal of Building Engineering, 2021.

- Erfani, A.; Khanjar, H. "Large Language Models for Construction Risk Classification: A Comparative Study." Buildings, 2025.

- Rehman, A. "The Role of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Risk Management for Sustainable Bridge Projects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Journal of Sustainable Development and Policy, 2025.

- Centroid. "3 Ways To Create Guardrails for Your AI Initiatives: Expert Insights With Centroid Partner Guardrail Technologies." Centroid, 2025.