The demonstration, covered by TechRadar, helped frame what many described as a trusted-execution-environment security crisis in 2025.

Weeks later, a team from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Purdue University widened the scope with TEE.fail, described on the project site tee.fail, showing that a similar bus-interposition approach works on newer DDR5 platforms and breaks Nvidia confidential-computing GPU attestation.

Together, the proofs of concept challenged long-standing assumptions about physical attackers being outside the threat model for trusted execution environments, or TEEs, the hardware feature set that promises to shield data from cloud operators themselves.

Key Findings

- Low-cost interposer boards on DDR4 and DDR5 can intercept encrypted memory traffic and recover cryptographic material, including attestation keys, on Intel SGX/TDX and AMD SEV-SNP systems.

- Wiretap and Battering RAM target DDR4 platforms, while TEE.fail generalizes the attack to DDR5 servers and to Nvidia GPU confidential-computing attestation.

- Once attestation keys are extracted in lab conditions, attackers with brief physical access can forge valid quotes, launch fake confidential VMs or decrypt protected workloads.

- Intel and AMD acknowledge the research but state that physical interposer attacks remain outside TEE security guarantees as of 2025.

- Proposed responses range from stricter physical controls to new designs with memory-integrity trees, probabilistic encryption and external key-management hardware.

Interposer Boards Challenge Hardware Assumptions

At the heart of each attack is a slim printed-circuit board that slots between the DIMM slot and the memory module. The interposer taps the command, address and data lines on the DRAM bus, letting researchers observe deterministic AES-XTS ciphertext patterns long enough to build a lookup table of plaintext values.

The TEE.fail project site tee.fail publishes schematics and notes that DDR5 is even easier to tap because each module exposes two half-width channels. While vendors had assumed that soldering such a device inside a data center would be impractical, the researchers report that the technique can be applied within a short maintenance window. The TEE.fail interposer is designed as a passive probe that records traffic rather than modifying it.

The interposer enables attacks without software detection or log entries, as described by the research teams. Once keys are recovered from the DDR4 or DDR5 bus, the researchers show how to forge SGX or TDX quotes, launch fake confidential virtual machines, or decrypt snapshots offline. That capability undermines key-management workflows that release secrets only after verifying a hardware quote, including confidential databases and secure multiparty computation services.

What Trusted Execution Environments Promise

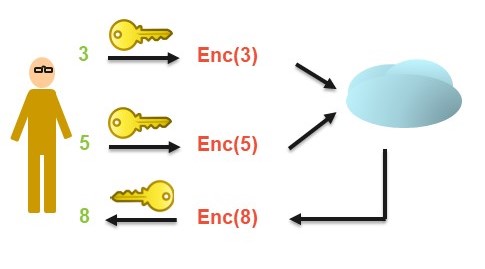

In a trusted execution environment, code and data run inside an enclave that is isolated from the host operating system. Memory pages that leave the processor package are encrypted with AES-XTS, and a vendor-signed attestation quote allows a remote party to verify that the expected code is loaded.

Intel markets this as Software Guard Extensions for process-level enclaves and Trust Domain Extensions for whole virtual machines, while AMD’s counterpart is Secure Encrypted Virtualization with Secure Nested Paging. In theory, even the cloud operator cannot read or tamper with the enclave.

For typical cloud customers the flow is simple: they start an enclave or confidential virtual machine, present the quote to a key-management service, receive secrets and proceed.

The model assumes that attackers can compromise firmware or the hypervisor but cannot observe the high-speed bus that links CPU and DRAM. The 2025 interposer work collapses that assumption because the memory-encryption design on the external DRAM bus in the implementations studied does not provide strong integrity or freshness guarantees against a physical probe, and the encryption mode repeats the same tweak for a given physical address.

More Technology Articles

Why Deterministic Encryption Falls Short

AES-XTS was chosen for speed; each cache line is encrypted deterministically as a function of the line address. If the same plaintext reappears at the given address, the ciphertext repeats. By writing known patterns from inside the enclave or VM and watching the bus, researchers built a dictionary that maps ciphertext blocks to plaintext bytes.

Because AES-XTS–style memory encryption on its own provides only limited confidentiality and no integrity or anti-replay protection against physical attackers, alias-based interposers like Battering RAM can also replay stale ciphertext or inject modified data without being rejected by the processor. In contrast, the DDR5 interposer used in TEE.fail is operated passively, but it still suffices to recover secret attestation keys and other sensitive data.

The twin Wiretap and Battering RAM techniques exploit that weakness in different ways. Wiretap is passive: it records encrypted traffic on DDR4, waits for repetition and infers keys by building a ciphertext-to-plaintext dictionary. Battering RAM is active: it manipulates electrical signals and exploits physical aliasing to gain arbitrary read and write access into SGX-protected memory and to break SEV-SNP attestation. Both attacks require physical access but no firmware exploit, and they show that physical access to the memory bus can bypass the intended protection of memory encryption.

From Wiretap to TEE.fail: Escalating Proof-of-Concepts

The first public demonstrations targeted third-generation Intel Xeon Ice Lake servers and AMD EPYC parts with DDR4 memory. The Battering RAM work from KU Leuven and the University of Birmingham showed that a hand-soldered interposer built from roughly 50 dollars of components could intercept and replay encrypted traffic while remaining transparent to system software, extracting sensitive enclave data and undermining SEV-SNP’s attestation guarantees.

According to TechRadar and KU Leuven’s own summary, the researchers used the setup to expose data that was meant to remain confidential under SGX and SEV-SNP.

TEE.fail broadened the method to fourth- and fifth-generation Intel Xeon silicon running DDR5 and to Nvidia H100 GPUs in confidential-compute mode. The authors reported that they could recover per-CPU provisioning certification keys and related attestation keys and then forge quotes that appeared valid to remote services. This meant that an attacker with brief physical access could impersonate a genuine enclave or confidential virtual machine and obtain secrets from services that trusted the attestation alone, and could in turn break Nvidia’s GPU confidential-computing attestation chain.

According to the Intel security announcement, the research does not change Intel’s position that attacks requiring a physical interposer are outside the scope of its threat model for SGX and TDX.

AMD adopted a similar stance in Security Bulletin AMD-SB-3040, stating that it does not plan to provide mitigations because physical vector attacks are out of scope for SEV-SNP. Vendors therefore classified such physical attacks as outside their formal security guarantees.

Academics and practitioners note that privileged insiders, supply-chain actors or state-level adversaries may already possess the skill and access needed to deploy such hardware. KU Leuven’s news release outlined how short maintenance windows or decommissioning cycles can provide opportunities to install an interposer board without long outages.

Industry Reaction and Interim Defenses

For operators of confidential-computing services, the interposer work has practical consequences. Many key-management systems were designed to treat a valid attestation quote as a sufficient signal that it is safe to release encryption keys or other sensitive material. Once it became clear that an attacker with physical access could forge these quotes, security teams began reassessing how much trust to place in TEEs on their own.

Security teams may adopt a layered approach that includes tamper-evident seals on DIMM clips, security cameras focused on open-chassis events and two-person maintenance rules. These controls do not prevent an attack outright but can reduce opportunities for undetected hardware modification and provide audit trails when chassis access occurs. They are relatively low-cost steps that align with standard data-center physical security practices and echo the mitigations suggested by the TEE.fail authors.

Software architects may also move critical secrets into external hardware security modules and use enclave attestation only as an additional signal, not the sole condition for key release. In this design, the TEE still reduces exposure to remote software attacks, but loss of a single attestation key no longer gives full access to application secrets. These measures reduce the impact of a compromised attestation key but do not restore the original hardware security goal of making memory snooping infeasible.

Rethinking Confidential Computing’s Road Map

Long-term fixes center on adding integrity trees, hierarchical message-authentication codes that verify every cache-line fetch from DRAM. With an integrity tree or similar integrity-protected memory-encryption mode, the processor can detect if an interposer replays stale data or injects modified ciphertext, at the cost of extra memory traffic and latency.

Researchers also describe probabilistic encryption that injects per-write randomness, making ciphertext patterns useless to a passive probe but increasing implementation complexity.

Another proposed direction is to move more sensitive data onto on-package high-bandwidth memory. Shortening the electrical path between compute cores and memory reduces the locations where an attacker can insert an interposer without detection. This approach does not eliminate the need for strong encryption and integrity but narrows the exposed surface to a smaller and better-controlled part of the system.

A parallel track explores hybrid models that combine TEEs with multiparty computation or threshold signatures. In that design, an enclave still proves code identity, but critical operations require a quorum of keys held in external hardware security modules. This approach accepts that a single node’s memory can be monitored yet raises the bar for a successful theft to compromising multiple machines in different physical locations.

A New Trust Boundary

The 2025 interposer experiments clarify the gap between vendor threat models, which treat physical access as out of scope, and customer expectations that TEEs would resist insider access.

For now, a trusted execution environment defends against remote software exploits, not attacks that open the chassis and insert hardware on the memory bus. Until deterministic encryption is replaced or strengthened with integrity checks on external memory, organizations need to treat off-package DRAM as untrusted and plan for layered key control.

That adjustment affects key-management flows, incident-response plans and compliance language. It also illustrates a basic security lesson: encryption without integrity protection leaves systems exposed. Cloud providers continue to offer confidential-compute options, but recent research defines clearer limits for those features and sets concrete requirements for the next generation of designs.

Sources

- Udinmwen, E. "Battering down the doors – this $50 hacking kit is enough to break Intel and AMD’s toughest chip defenses." TechRadar, 2025.

- De Meulemeester, J.; et al. "Battering RAM." University of Birmingham & KU Leuven, 2025.

- Chuang, J.; et al. "TEE.fail: Breaking Trusted Execution Environments via DDR5 Memory Bus Interposition." Georgia Institute of Technology & Purdue University, 2025.

- Intel Product Security Team. "TEE.fail Security Announcement 2025-10-28-001." Intel, 2025.

- Intel. "More Information on Encrypted Memory Frameworks for Intel Confidential Computing." Intel, 2025.

- AMD Security Engineering. "Security Bulletin AMD-SB-3040." AMD, 2025.

- KU Leuven COSIC & DistriNet. "KU Leuven research exposes fundamental hardware flaw in highly protected cloud servers." KU Leuven, 2025.