The Toyota Production System, or TPS, applied a set of linked practices rather than a single tool. According to the TPS lexicon maintained by the Lean Enterprise Institute, core ideas include eliminating waste, just-in-time production, continuous improvement known as kaizen, Jidoka (built-in quality through stop-the-line capability), and respect for people. In lean terminology, “eliminating waste” is often framed through the “three Ms”: muda (waste), mura (unevenness), and muri (overburden).

Over time, these manufacturing ideas influenced how organizations outside the automotive sector managed complex work. A 1986 article in Harvard Business Review documented development teams that applied TPS-like principles, and those observations later informed early Agile software frameworks, the Agile Manifesto in 2001, and Lean Software Development in 2003.

Key Developments in the TPS-to-Agile Lineage

- TPS emerged at Toyota in the late 1940s, evolving through the 1950s and 1960s with a focus on eliminating waste, just-in-time flow, kaizen, Jidoka, and respect for people.

- Takeuchi and Nonaka's 1986 Harvard Business Review article introduced iterative rugby-style teams to Western managers and highlighted practices later linked to TPS concepts.

- Jeff Sutherland implemented the first Scrum in 1993 and later referenced the 1986 HBR research in accounts of Scrum's origins.

- Seventeen practitioners codified related values for software work in the 2001 Agile Manifesto.

- Lean Software Development (2003) translated TPS principles such as waste elimination and built-in quality into software-specific practices.

- Contemporary Agile and DevOps approaches continue to apply pull-based flow, feedback, and continuous improvement to software delivery.

Foundations on the Factory Floor

On Toyota assembly lines, Jidoka allowed workers and machines to stop production when a defect appeared. The Lean Enterprise Institute notes that this approach built quality into the process instead of relying only on end-of-line inspection.

Stopping the line was costly in the short term, so teams also traced root causes and adjusted standardized work. That cycle of detection, pause, and correction created a structured feedback loop between daily operations and process design.

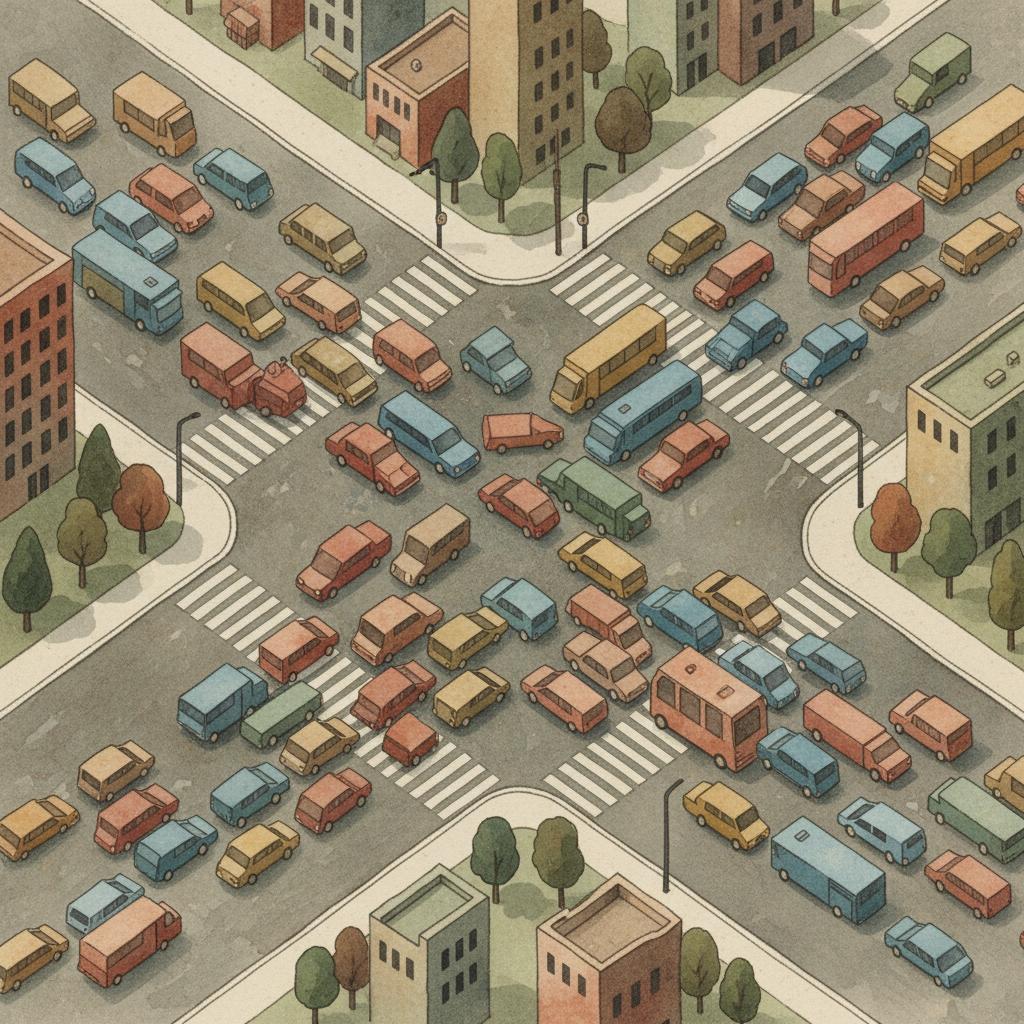

TPS also limited inventory and work in process through just-in-time production. Parts were produced or delivered only when the next step required them, in the needed quantity, which reduced inventory and exposed problems in scheduling, capacity, or quality more quickly.

Continuous improvement encouraged small changes proposed by those doing the work rather than infrequent top-down redesign.

Respect for people supported this pattern by framing workers as sources of insight into how to refine equipment layouts, motion, and task sequencing. These practices made TPS a system for coordinating information, materials, and human judgment.

That combination later made it attractive as a reference point for knowledge work such as product development and software engineering.

More Technology Articles

Publishing the Bridge to Product Development

In 1986, Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka examined product development at several Japanese and Western companies. Their article "The New New Product Development Game" in Harvard Business Review contrasted sequential handoffs with a more integrated style of work.

"Under the rugby approach, the product development process emerges from the constant interaction of a hand-picked, multidisciplinary team whose members work together from start to finish."

The authors described teams that advanced through overlapping phases, shared responsibility across disciplines, and learned quickly from experiments. This description provided managers with a vocabulary for cross-functional teams, iterative progress, and goals that persisted across phases.Although the article focused on product development rather than factory operations, it reflected ideas that aligned with TPS, including autonomous teams and rapid feedback.

Because it appeared in a general management publication, the work reached a broad audience—including managers responsible for complex development efforts (software among them) who were looking for ways to reduce schedule slippage and avoid costly rework.

Scrum: Early Software Translation

Jeff Sutherland later cited the Takeuchi and Nonaka study as a key influence on the first Scrum implementation in software. In an account of Scrum's origins on Scrum Inc., he describes forming a team at Easel Corporation in 1993 that worked in short, time-boxed iterations.

"The first Scrum implemented all the practices we know as Scrum today plus all of what later became known as XP practices."

The early Scrum implementation emphasized a fixed-length cycle, a prioritized backlog of work, and regular inspection of both product and process. Practices such as reviews and retrospectives created scheduled points to adjust plans based on what the team had learned.Sutherland's retrospective accounts link these ideas to the 1986 Harvard Business Review study and to manufacturing concepts such as limiting work in process. Scrum framed these elements as a lightweight framework for managing complex software projects rather than a set of detailed engineering practices.

Agile Manifesto: Codifying a Philosophy

By 2001, several practitioners who had tried iterative methods, including Scrum, gathered in the United States to summarize shared patterns. The resulting Agile Manifesto, published on the Agile Manifesto site, set out four value statements that prioritized people, working outcomes, collaboration, and responsiveness.

The values contrasted individuals and interactions with formal processes and tools, working software with comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration with contract negotiation, and responding to change with following a plan.

The document did not prescribe a specific method, which allowed teams to adapt the ideas within their own constraints. Twelve supporting principles elaborated on these values with guidance on delivery cadence, customer involvement, and technical quality.

Short delivery cycles and regular reflection parallel aspects of TPS such as one-piece flow (moving work in small batches) and kaizen, while the focus on simplicity aligns with reducing non-value-adding work.

Although the manifesto did not name TPS or manufacturing, readers and later commentators have noted that its focus on empowered teams and feedback-driven change fits with the logic of lean production. The document provided a shared reference that helped Agile ideas spread across software organizations of different sizes.

Lean Software Development: Explicit Adaptation

In 2003, Mary and Tom Poppendieck published Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit, which drew directly on the language of lean production. A summary from Scrum Alliance describes how the book translated concepts such as built-in quality, deferred commitment, and amplifying learning into principles for software teams.

"Design, implement, feedback, improve."

The book framed software development as a flow of ideas from concept to working code, with feedback guiding each step. It emphasized reducing waste in forms such as partially done work, extra features, and delays, echoing TPS’s focus on muda within the broader “three Ms” lens.Lean Software Development also highlighted the financial impact of faster, smoother flow. By tying cycle time and work in process to outcomes that leaders could measure, it gave executives a way to connect engineering practices to broader organizational goals.

These adaptations made the link between TPS and Agile explicit rather than implicit. They also showed how principles developed for repetitive manufacturing could be reinterpreted for work that involves uncertainty and learning.

Ongoing Legacy in Modern Toolchains

Later approaches in software engineering extend this lineage by integrating development, testing, and operations into a single delivery pipeline. Practices such as continuous integration and continuous delivery apply the idea of small, frequent changes that can be tested and deployed with controlled risk.

Many teams now visualize work as items moving through defined stages, limit the amount of unfinished work, and use automated checks to stop the flow when quality issues appear. These mechanisms echo just-in-time coordination and Jidoka in their focus on making problems visible early.

Modern reliability practices and incident reviews use structured reflection to adjust both code and process after failures. That approach resembles kaizen in that it treats problems as input to improvement rather than only as events to avoid.

Cloud infrastructure and monitoring tools have also made operational waste easier to see, for example when unused capacity or redundant services add cost without adding value. This visibility encourages organizations to treat infrastructure decisions as part of a broader lean system, not only as technical configuration.

Six decades after the key developments in the Toyota Production System, similar pull-based logic helps structure software projects that operate under uncertainty. As automation and new tools reshape programming work, the question for teams is how far these lean principles can continue to guide decisions about flow, quality, and human responsibility.

Sources

- Cleveland State University Pressbooks. "Applying Lean Six Sigma in Higher Education, Chapter 2: The Toyota Production System (TPS)." Cleveland State University, 2023.

- Lean Enterprise Institute. "Toyota Production System." Lean Enterprise Institute, 2024.

- Takeuchi, H. and Nonaka, I. "The New New Product Development Game." Harvard Business Review, 1986.

- Sutherland, J. "Early History of Scrum: First Scrum." Scrum Inc., 2004.

- Agile Manifesto Authors. "Agile Manifesto." Agile Alliance, 2001.

- Scrum Alliance. "Lean Software Development." Scrum Alliance, 2024.

- Sutherland, J. "Is it Scrum or Lean?." Scrum Inc., 2008.